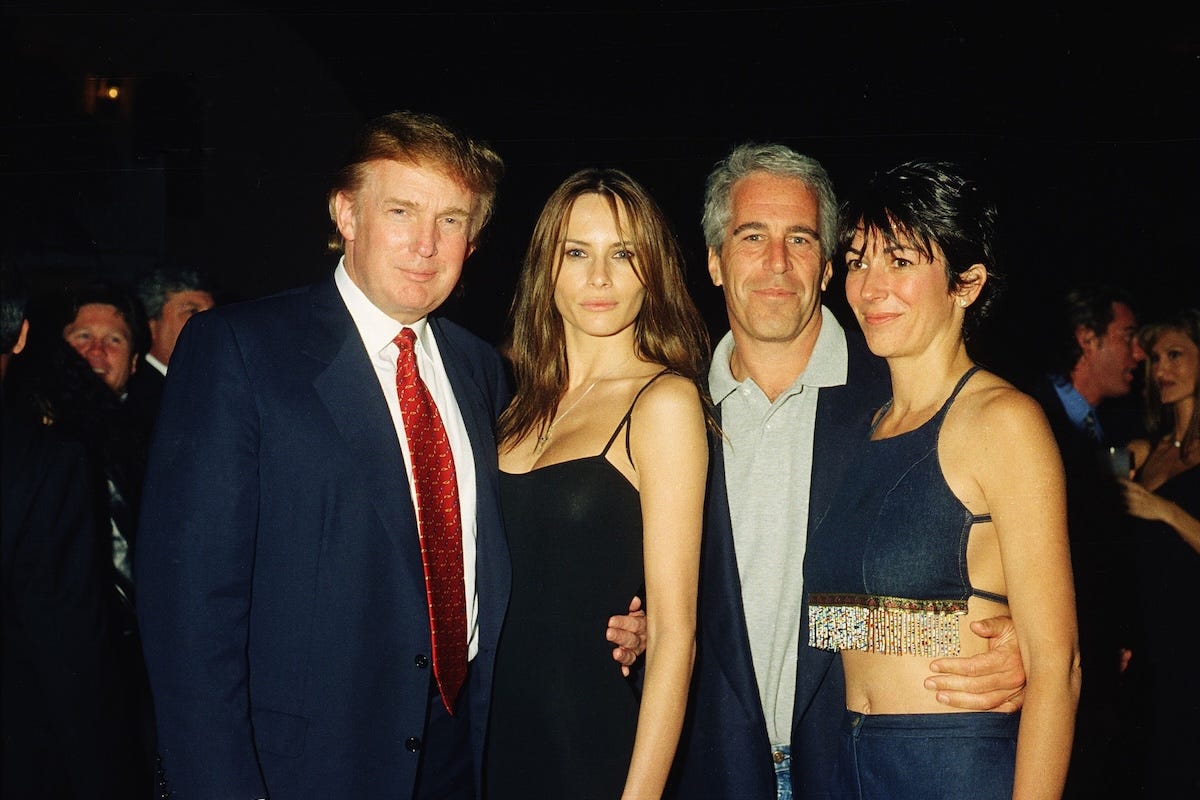

Donald Trump, Jeffrey Epstein, And The Construction Of Political Crisis

What we care about, and demand accountability for, is largely up to us.

Anyone can report anything they want to the FBI, which is why we don’t typically expect or allow law-enforcement officers to dump their case files on to the internet.

Some people are vindictive, some people are mentally unwell. Agents field farfetched accusations all the time, take notes as disturbed people rattle off delusions—and for the most part, the rest of us shouldn’t know about it. Not fair to the accuser, not fair to the accused.

The Jeffrey Epstein files, or the half of the files that the Justice Department has released thus far, contain plenty of this kind of documentation, including claims about Donald Trump that strain credulity. The Trump administration would like us to believe it’s all like this—at least as it pertains to Trump.

But it’s not true. Some of the accusations are credible.

The independent journalist Roger Sollenberger has been chasing down one particular accusation, which the FBI deemed credible, from a woman who:

Approached the Justice Department in July 2019, before Epstein’s suicide, accompanied by a lawyer;

Became one of Epstein’s underage victims as a teenager in the 1980s;

Claimed that, when she was 13-15 years old, Epstein introduced her to Donald Trump “who subsequently forced her head down to his exposed penis which she subsequently bit. In response, Trump punched her in the head and kicked her out”;

Was reluctant to implicate Trump for fear of retaliation;

Included an identical allegation against a “prominent, wealthy” New York man when she sued the Epstein estate in 2019;

Provided three further interviews with the FBI; notes from which are missing from the DOJ’s Epstein file database, but which are in the possession of Ghislaine Maxwell’s legal team.

Received a settlement from the Epstein estate.

This accusation alone falsifies claims by Pam Bondi, Susie Wiles, and other senior Trump officials that, while Trump’s name is all over the Epstein files, the files contain no evidence that he did anything wrong. When Wiles told Vanity Fair, “we know he’s in the file. And he’s not in the file doing anything awful,” it was a lie. When Bondi told Congress, “there is no evidence that Donald Trump has committed a crime,” it was perjurious.

And yet, for now at least, Sollenberger is way out ahead of his peers in mainstream news. They may catch up. But they are not inundating the White House with requests for comment or putting Sollenberger on television to discuss his reporting, or treating it as what it clearly is: a major development in the Epstein scandal.

In other words, and in the jargon of the politics business, this development is not “salient.” At least not yet. You have to be a news hound to know it exists. Not because reporters have deemed it unnewsworthy on the merits, but because they’re scared. Some degree of care—a great degree, even—is obviously appropriate given the magnitude of the accusation, and the stakes for this victim if she comes forward or is identified. But it goes beyond that. We’re witnessing fear of legal harassment. Of accusations of bias, Trump derangement syndrome, even defamation. Of threats of violence. We see it in television news segments on Trump and Epstein, which nearly all begin with a disclaimer that there’s no “evidence” that Trump engaged in “wrongdoing.”

It’s maddening. This is evidence! And “wrongdoing” is not a legal term. Trump has engaged in tons of “wrongdoing”—he palled around with someone well known to be a child predator! What we lack is smoking-gun proof of criminal activity.

Now, though, we have evidence of a grave crime. And yet the disclaimers continue.

We’re also witnessing, I think, a kind of flight response from a political class that’s unprepared to deal with the ramifications of what’s unfolding.

As I wrote several months ago, “it’s difficult for people in media and political leadership to openly discuss the implications of what we seem to be witnessing. Saying it out loud is genuinely unsettling. We’re talking about the possibility that the president of the United States raped children. The mere fact that we can’t be certain he didn’t do this is unsettling in itself. But we should stop tiptoeing around what we’re really trying to discover—we’re much less likely to get answers to the questions that really need answering if we’re too squeamish to ask them…. Democrats lack the power to begin impeachment proceedings. The best they can do is force the House to vote on an impeachment resolution—and I believe they should. More importantly, though, they have the power to articulate standards, and force Republicans to explain why their standards are so much lower: If Trump can’t be certain that his turpitude didn’t lead him into Jeffrey Epstein’s web of criminality, he should resign from office. If he doesn’t resign, Republicans should impeach him.”

Now is the moment. Now’s the moment to demand the missing files, to insist upon the appointment of a credible and independent special counsel, and to lay down a marker: that the existence of this accusation and the attempt to conceal it obligate Congress to consider impeaching Trump and removing him from office. Alternatively, we can all avert our gaze, until the public files it away as another “unproven allegation,” and the allegation loses its political potential.

Political professionals typically use the term “salience” to describe issues of public policy, and the extent to which they are on voters minds. They also frequently treat salience as an inherent property of issues.

Grocery prices are “salient” at the moment, and have been for years, because they’ve gone up and people are mad about it—they apparently expect their elected officials to do something. Gasoline prices become salient as they go up, and recede in salience as they go down.

In my mind, this conception is too narrow, on both ends. Any development that receives attention, and matters to people psychologically—enough to affect their views of politics in the short or long run—becomes salient. And the public can be persuaded (laudatory) or manipulated (derogatory) into imbuing developments with different meanings.

The politics of gas prices haven’t been constant over time. Nobody has ever liked having to pay more for things they really need, but the idea that price increases should make people mad at the president didn’t arise from the collective consciousness of the electorate. It was impressed upon them by political opportunists. Indeed, the political impulse to blame the president for high gas prices is a somewhat unique feature of the current era in which government has withdrawn from gas pricing, amid a parallel consensus that gas prices should be set by market forces.

I wouldn’t claim that the political salience of gasoline prices is entirely artificial. Elected officials set gas taxes, and pursue foreign policy objectives that can affect supply. But most of the time, political backlash over gas prices isn’t an organic product of rational thought, multiplied over tens of millions of people. It’s a product of media signals and partisan spin shaping mass perception.

Once you accept that issue salience is malleable, you start to notice it fluctuating everywhere.

For most of our history, consensus held that emergency management was a state and local issue. It took the New Deal, and the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation, and the advent of modern media to upend that consensus. We didn’t even have a Federal Emergency Management Agency until 1979. Once the consensus flipped, a new conventional wisdom took hold of politics: that political salience inheres to disasters and (thus) disaster response. After George H.W. Bush was criticized for the slow federal response to Hurricane Andrew in 1992, Bill Clinton sought to professionalize FEMA; he eventually made its director a member of the cabinet.

George W. Bush undid all this, prefiguring the humanitarian and political disaster of Hurricane Katrina, after which most of us thought the matter was settled. No president would be crazy enough to ignore natural disasters or place cronies in charge of responding to them. When Mitt Romney said he’d like to devolve FEMA to state and local governments and the private sector, it was understood as a gaffe.

Except… Donald Trump has made a mockery of federal disaster response, and it’s hardly proved a big liability for him. In some ways he personifies the idea that issue salience isn’t driven entirely by events and the organic emergence of public expectations. He fanned lies about the federal response to Hurricane Helene under Joe Biden, deepening the crisis through mass confusion, and making what should have been a politically neutral or even positive development for Democrats a negative and salient one. He operationalized the insight that made conservative activists so mad at Chris Christie in 2012, when he greeted Barack Obama in New Jersey and praised his administration’s response to Superstorm Sandy. These right-wingers were MAGA’s antecedents. They wanted Christie to increase the salience of that disaster, and turn it into a liability for Obama. Instead, he did the upright, professional thing, advanced the public interest—and Obama won re-election.

Trump simply abandons blue states, and blames them for not solving their own problems. As you read this, Trump’s administration is derelict in its response to a huge sewage leak into the Potomac River. We can see case by case that salience isn’t entirely inherent to issues, because basically none of Trump’s failures to address crises have proved particularly salient1.

All of this underscores the importance of media and media manipulation. When the Deepwater Horizon drilling unit exploded in Obama’s first term, Republicans were unconcerned about the facts of the matter. They called it “Obama’s Katrina.” Cable news networks tracked the oil slicks. It became a drag on his presidency until his energy secretary, a Nobel laureate, solved it as an engineering problem and assembled a ragtag group of experts to put theory into practice. Seriously!

Now think what would’ve happened if that problem had proved insoluble, or much harder to solve? Would it have ended Obama’s presidency? Should it have? It wasn’t his fault! And yet in his rectitude and caution, Obama probably wouldn’t have had it in him to place the onus on the gulf states. To say, in essence, ‘this is a problem of Republican governance and of a Republican friendly industry writing its own rules, then passing the buck to the feds when it all goes to hell, so figure it out yourselves!’

In his post-presidential memoir, he writes, “what I really wanted to say before the assembled White House press corps [was] that MMS wasn’t fully equipped to do its job, in large part because for the past thirty years a big chunk of American voters had bought into the Republican idea that government was the problem and that business always knew better, and had elected leaders who made it their mission to gut environmental regulations, starve agency budgets, denigrate civil servants, and allow industrial polluters do whatever the hell they wanted to do… I didn’t say any of that. Instead I somberly took responsibility and said it was my job to ‘get this fixed.’”

It all became moot when the spill was contained. But you can see how this political asymmetry could have transformed a disaster with roots in the GOP and the corporate world into an existential political crisis for Democrats. A disaster like that would have been salient no matter what, but its political meaning wasn’t inscribed anywhere.

What’s any of this got to do with Epstein?

The broad Epstein files scandal is already salient. But the question of how it will ultimately be understood, and where political accountability will fall, is still up for grabs. Is this mostly a story about elite impunity, bipartisan failure, bureaucratic incompetence and/or corruption? Or will it be just as much a story about how the country was deceived into electing a sex predator angling to cover up his own crimes and got caught. Where we look back and say there was a specific moment when the government had to decide whether there would be any consequences for this depravity, and we, the public, got to see in real time who tried to do the right thing and who sided with the dregs of humanity?

Republicans are trying, very hard, to contain the story to the first realm. What I am suggesting is that Democrats work just as hard and just as creatively to influence what becomes salient, and what the public thinks should be done about it. With respect to the Epstein files, and everything else.

We can’t criminalize GOP bad faith, but I will die screaming that making it politically costly for Republicans to operate in this way is the key to stabilizing American democracy; that failure to try has brought us predictably to the verge of civic collapse.

Democrats can begin changing that right now. They could demand financial restitution for the damage Trump has doned to Minneapolis and Minnesota. Trump’s abandonment of blue-state disaster victims is a dereliction of duty and a form of theft. If the elected officials who quietly tolerate this kind of abuse, or complain about it impotently, faced similar affronts in their personal lives, would they act like this—like Obama suffering heckles from the cheap seats during the gulf oil spill?

What would you do? If you, say, signed a contract and paid a deposit for someone to do an important job, and they took the money and ran? How would you react? Presumably you’d fight, yes? You might briefly offer the benefit of the doubt. Try to rule out the possibility of misunderstanding. But before long you’d escalate. File a police report. Detail the ripoff on Yelp. Sue to get money back. Right?

Republicans swing past all this into insincere theatrics. But they still respond to events more legibly than Democrats, who tend to believe their best move is to suffer indignity, and hope to pivot to health care. They’d be better off reading How To Win Friends And Influence People than they are following rehashed advice from myopic pollsters.

There are, I must note, times when Democrats comport themselves in dignified ways, just as there are times when Republicans flail impotently. Pam Bondi behaved much like a panicky Democrat last week when she implored the public to ignore Epstein and focus instead on the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Democrats finally managed to increase the salience of health care in a politically advantageous way by shutting down the government last year. But in the normal course of things, Democrats will retreat from confrontation, and Republicans will wrest control of public discourse with extreme aggression. Democrats surrendered the shutdown while they were ahead; Trump will bomb Iran or lay siege to another U.S. city if he thinks it’ll bring him fleeting relief from Epstein scrutiny.

The lesson is not that Democrats should deceive and wag the dog, but that their conduct provides critical signals to the public about the meaning and importance of developments. A party actively engaged in shaping opinion can make the public blame the president for an oil disaster he had nothing to do with; a party that shirks these obligations can inadvertently help a dishonest president brush off a credible allegation of child rape.

COVID proves both the exception and the rule. It was one of the most salient events in modern history. The public disapproved strongly of Trump’s response. He did lose the ensuing election, but did so while increasing his vote share. And by 2024 all was forgiven.

"A party actively engaged in shaping opinion can make the public blame the president for an oil disaster he had nothing to do with; a party that shirks these obligations can inadvertently help a dishonest president brush off a credible allegation of child rape."

This on stilts on acid from Hell. Dems have to stop asking the public how it feels and reacting in response to that. They should TELL the public how THEY feel (and, by implication, how the public should feel), and offer leadership to respond accordingly. It's not complicated or subtle. And fa chrissakes, we're talking about child rape. If that, with regard to a POTUS (or anyone else), isn't "salient," what is? Or do they need more than forty years of Republican bad faith and mendacity to finally really get mad?

Article after article (rightly) talks about how most Dems need to work much harder at shaping public opinion but doesn’t really answer the question of how we get them to internalize this.

It appears to me too many remain too scared of offending some random voters to factually and clearly state what’s going on with this regime and the GOP, and not just as it pertains to Epstein.

The so called MSM isn’t going to do the heavy lifting for Dems the way they do for the GOP, Democrats are going to need to force them to report on it.