Obama and Biden Were Not That Different

Their intraparty fans and critics dislike each other and jockey for influence, but practical politicians don't think that way.

The political value of Kamala Harris’s Tuesday speech on the capital ellipse was nearly all visual—overflow crowds to the horizon, the ghost of the White House looming behind her.

Here, though, I want to focus on the text of her remarks, and specifically the least galvanizing section of them: the policy laundry list. In drawing a contrast with Donald Trump’s agenda, Harris promised to:

“enact the first-ever federal ban on price gouging on groceries, cap the price of insulin, and limit out-of-pocket prescription costs

“fight to help first-time home buyers with your down payment, take on companies that are jacking up rents, and build millions of new homes…cut red tape and work with the private sector and local governments to speed up [home] building;”

“fight for a child tax credit to save them some money, which will also lift American children out of poverty;”

“allow Medicare to cover the cost of home care so seniors can get the help and care they need in their own homes.”

This was a rote exercise for a Democratic campaign. Elections affect policy, so Democrats talk about issues. The issues are the things people say they think and care about most in their lives. But in the high drama of a presidential campaign, the bullet-points themselves serve as politically inert boilerplate: I care, and to prove it, here’s some stuff I’d do.

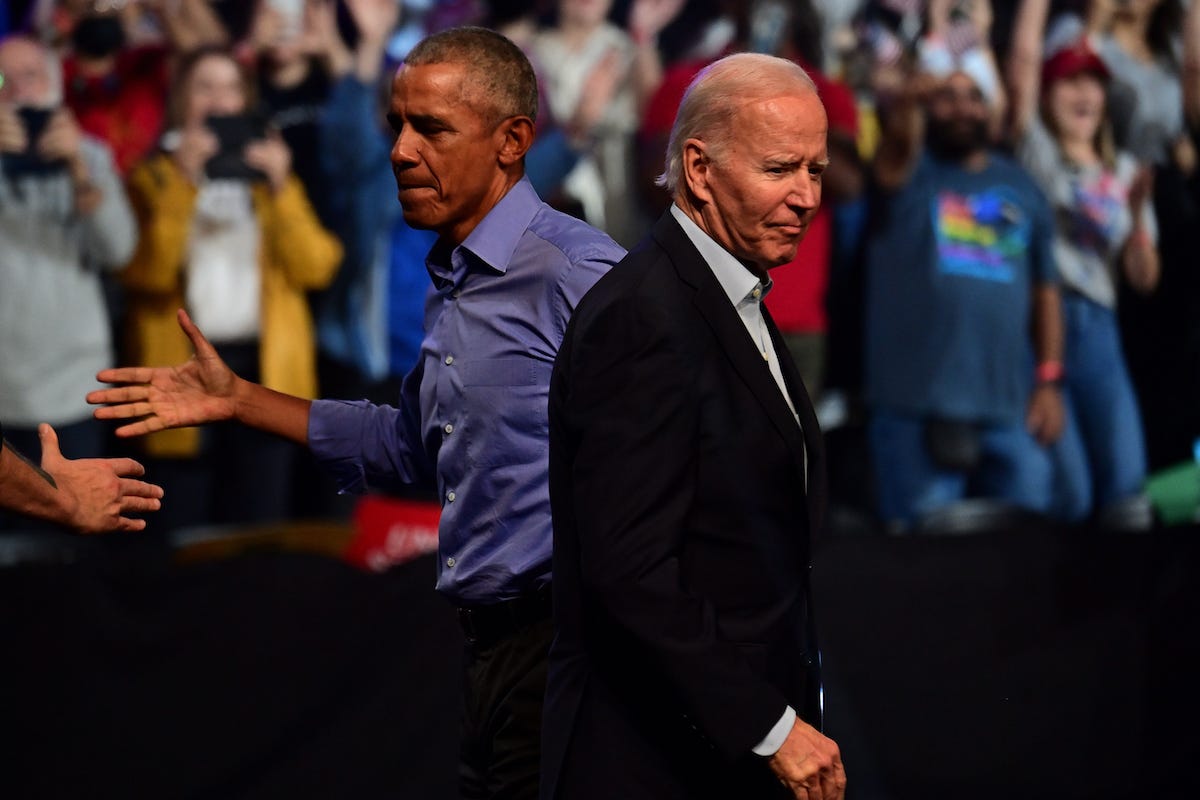

In their continuity with Obama and Biden era Democratic policymaking, though, these particular ideas helped me clarify my thinking about an ongoing factional dispute between moderate and progressive liberals over the soul of the Democratic Party. Really, it’s a fight over whether Barack Obama or Joe Biden had the superior ideology or approach to wielding power.

“Bidenism brought Kamala Harris and the Democrats to the brink of catastrophe. Obamaism can save them,” reads the subheadline of a recent essay by the liberal writer Jonathan Chait.

“Contra Jon Chait,” responded the progressive writer Harold Meyerson, “Biden’s economic progressivism has been both historic and (had he only been able to explain it) good politics.”

This “my guy”/“no, my guy” debate has been simmering for months if not years, and I find its intensity a bit mystifying. When you strip away animus and factional jockeying, there just isn’t a ton of first-principles disagreement, and there shouldn’t be much disagreement over the electoral implications of either view.

It’s not like the grueling fight between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton over whether the U.S. should scrap its health-insurance system and replace it with Medicare for all—a binary choice between two philosophies, promising two political trajectories that bear no resemblance to one another. Biden and Obama surely have different ideas and hobbyhorses and theories of governing, as do progressives (who take special interest in curbing corporate power) and moderates (who take special interest in income redistribution). But the ideas that supposedly encapsulate the differing Obama and Biden worldviews are all broadly liberal, and perfectly reasonable for Democrats of all kind to champion. The big question surrounding them isn’t “which ideas reflect a better understanding of the country’s political economy” or even “which add up to the most successful political program?” but “what does the country need most at the moment, and what is in our power to do?”

ANTITRUST BUT VERIFY

Even before Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, the broad left was fishing around for unifying ideas. Health-care reform was done, though at a big political price. Progressives were profoundly divided over whether Democrats should expand on Obamacare or transform it into a single-payer type system, which decreased the chances that the next Democratic president would tackle health-care reform of any kind. Climate change was still an urgent priority, but a political powder keg, too.

The issue spaces that generated the most consensus at the time centered on reducing wealth concentration and inequality. Just as Elizabeth Warren had strengthened financial regulation—and united Democrats—by creating a new and innovative regulatory body (the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) next-generation Democrats could further protect people from corporate abuses through the passage and reinterpretation and enhanced enforcement of antitrust laws.

My reporting back then centered on the party’s post-Obama trajectory, but my notes included background comments from multiple disconnected sources who told me Clinton, the high priestess of neoliberalism, would likely have offered an appointment in her administration to antitrust champion Lina Kahn—now Joe Biden’s Federal Trade Commission chair, who was then still in her 20s.

Alas, it wasn’t meant to be. But after Donald Trump won that election, and Democrats descended into bitter recriminations, building internal consensus became a matter of real political urgency, not mere musing about future policy initiatives.

Today, because of the factional infighting I described above, antitrust enforcement codes as a “progressive” idea, crowding out “liberal” ones, but at the time and even now, the idea of taking on wealth concentration had buy in across the party—from progressive icons like Warren to moderate presidential hopefuls like Amy Klobuchar and Cory Booker. It bridged the policy divide and provided an answer to the improvident question of how Democrats could reclaim economic populism from Trump.

There's very little sense in which this amounted to a progressive triumph over neoliberalism. Liberal and progressive issue activists are always jockeying for pride of place in the Democratic agenda, but these ideas are no more liberal-democratic than social-democratic. Obama may have been unnecessarily cool to them (or perhaps you believe Biden has been unnecessarily solicitous of them) but the main explanation for the difference is that the issues hadn’t ripened when Obama took office, and the country had other exigent needs that might have gone unaddressed if he’d made busting trusts and monopolies his top priority.

After Joe Biden beat Trump and became president, you might say he made a break with Obamathink, but I think (and my reporting suggests) it’s more accurate to say this is where the party drifted due to circumstance, well before Biden’s presidency. Clinton’s presidency would have gone in this direction, too, and I imagine that if Obama had been allowed a third term in office, he would’ve gone there as well.

If the so-called “new progressive economics” seems to have played an outsized role in Biden’s presidency, it’s in part because the ideas had Democratic broad buy-in (presidents are supposed to unify their parties!) and in part because his narrow congressional majorities made it difficult for him to pass big, permanent, partisan reforms. Obama also leaned heavily on his administrative power, but only after he lost his supermajorities. He promulgated big, ambitious reforms of his own, including new immigration and environmental policies that generated significantly more partisan backlash than any Biden initiative, save perhaps student-loan forgiveness.

But by 2021, antitrust reform per se didn’t serve the same urgent political purpose it did in the wreckage of 2016. Trump had been defeated, and his failed presidency left new, different wreckage in its wake. The most ambitious and politically salient aspects of of Biden’s agenda all stem from that cleanup effort.

Every part of this story turns on circumstance. The country’s needs change over time. Whether the federal government should focus on the “predistribution” of income (by weakening employers and empowering workers) or “redistribution” (through taxes and transfers) should really turn on questions like: What’s happening in the country right now, and can Democrats pass legislation to address any of it? Not, what is the most compelling critique of American capitalism? Or, what would my favorite Democrat do?

NEEDFUL THINGS

If Harris wins the presidency next week, the story will be much the same. Her ambitions will be contingent on the needs of the country and the partisan makeup of Congress.

If she defies odds and wins with a governing trifecta, she’ll be blessed with real berth to make policy reforms outside the confines of a national emergency.

And I think you can see from her own laundry list that her agenda resembles both Obamathink and Bidenthink, not because she’s meticulously split the difference, but because the differences aren’t so vast to begin with, and the country’s current needs necessitate a combination of approaches.

If anything, the big lesson Harris should take away from her predecessors’ experiences is that her policy agenda and political standing aren’t so tightly linked. Obama was not rewarded for the Affordable Care Act right away—quite the contrary, in fact. His best move politically would've been to do more Keynesian stimulus and less permanent reform of any kind. But he was re-elected, left office popular, and has become one of the most admired figures in America, transcending the country’s polarized politics.

Biden, by contrast, faced conspicuously little blowback for his policy reforms per se. There is no mass movement to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act, and the GOP’s desire to do so is if anything a political liability for them. Bye-bye $35 insulin. Democrats did really well in the 2022 midterms given their incumbency, but Biden nevertheless became so unpopular that he had to withdraw from his own re-election campaign.

Because all along Biden's political albatross has been his age.

This is the huge, glaring factor that progressives and moderates gloss over in this debate. In other contexts, most everyone agrees that but for being 81 years old and (thus) debilitatingly marble-mouthed, Biden would still be running for president, and significantly more popular than he is. Yet for purposes of this debate only everyone sets the craziness we just lived through off to the side. Biden’s intraparty critics in particular will cite his political unpopularity to discredit the progressive aspects of his agenda, as if his age were a trivial factor.

“The issue of Biden’s age, in some respects, has obfuscated the danger that the Democrats find themselves in,” Chait writes, obfuscating in his own way how little connectivity there is between Bidenomics and Biden’s unpopularity.

KAM BEFORE THE STORM

Harris is not 81 years old and has proposed no reforms as ambitious as Obamacare. I suspect her political challenges in office will be more exogenous. But she should build her actual “to do list”—the stuff she spends the most time and effort on—around need in the country. It's good that housing and Medicare benefit enhancements are on that list—if I were her I'd put thought into how to disempower the country’s ascendant fascists. But at full employment, in the aftermath of inflation, and with either a divided Congress or small congressional majorities, she's likelier to get sucked into a deficit-reduction stand-off with Republicans than into a big intramural debate over price-gouging vs. child tax credits.

That is to say, I think Harris’s presidency, should we be so lucky, will serve to underscore just how territorial and overheated the factional infighting of the Biden years has been.

In that same ellipse speech, Harris made the most practical statement to date about how her administration would differ from Biden’s.

“My presidency will be different because the challenges we face are different,” she said. “Our top priority as a nation four years ago was to end the pandemic and rescue the economy. Now our biggest challenge is to lower costs, costs that were rising even before the pandemic, and that are still too high.”

Whether she’s right or wrong about America’s biggest challenge (for what it’s worth, I think she’s wrong) this is a much better way to think about governing than totemic contests between ideologies and hero figures.

If we could rerun the Obama presidency with Biden at the helm, and the Biden presidency with Obama at the helm, the status quo would surely look somewhat different. But it’d hardly be unrecognizable. Imagine a world where Biden gets a bad rap from progressives for failing to shoot the moon on comprehensive health-care reform, and moderates bristle at Obama for making enemies of authoritarian fat cats on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley. It isn’t that hard if you try!

The biggest mistake that President Obama and his attorney General Eric Holder made was not prosecuting the banksters that brought on the Great Recession in 2008. If they would have initiated consequences against those people, Trumpism never would have happened. I was directing a nonprofit at the time and was dealing with a lot of folks that were losing their homes and jobs. The anger was palpable. I almost lost my house. Millions of Americans suffered horribly and not one of those 1%ers EVER went to jail. That was the catalyst that brought Trump into our lives.

Agree that costs, per se, aren't the biggest challenge. Real wages have risen faster than inflation; real costs aren't up. But, oligarchic concentrations (in, as just one example, the meat packing industry) support price gouging. Even when those prices are nonetheless affordable to most, using price motivations to break up the near-monopolies through which oligarchs (Bezos, the Waltons, Musk) strangle our nation and world is, if not our biggest challenge, somewhere close to it, and intertwined with other large challenges, such as climate.