Graham Platner And The Perils Of Infighting

Chuck Schumer should bow out and let this guy cook.

I’ve been at a loss for anything novel to write about Graham Platner, the buzzy oysterman who’s running for the Democratic Senate nomination in Maine.

He seems like a good candidate. More to the point, he represents a stronger archetype for rural-state candidates than Democrats typically prefer. Less experience and caution, more Common Sense™️ and self-knowledge.

And, of course, if he goes on to win the nomination, I’d want him to defeat Susan Collins, the incumbent Republican. But none of that’s very interesting or insightful.

Watching throngs of Mainers heckle and boo Collins, though, and reflecting on her plummeting approval polls, I realized there is a point worth making: Chuck Schumer should accept defeat here. He should stop trying to recruit Janet Mills, the state’s 77-year-old governor, or anyone else to run against Platner. He should definitely not try to recruit Jared Golden—the Maine House Democrat who wants to write the filibuster into the Constitution. He should give up on his dream of recruiting some more seasoned politician of the kind Collins has defeated every six years for a bajillion cycles in a row, and give everyone in the Democratic coalition a fair and unspoiled test of left-populist appeal.

An answer to this question—are blue-collar, pro-labor progressives better candidates than conventional moderates?—would provide the party genuinely important information about what kind of candidates they should hope to nominate in reach states, and maybe even for president, going forward.

You can think of it as giving everyone a second bite at the John Fetterman apple. Four years ago, the entire Democratic establishment lined up to defeat Fetterman in the Pennsylvania Democratic Senate primary, in favor of Conor Lamb, who was, at the time, the archetypal establishment candidate.

Fetterman had supported Bernie Sanders in 2016; in 2022 he nailed the progressive tough-guy schtick. He beat Lamb handily, then beat his Trump-backed general-election opponent, Dr. Oz. But of course, right before the election he suffered a catastrophic, personality-altering stroke, and it confounded the whole experiment. Would Fetterman have done better or worse in that race if he hadn’t spent election night in the hospital? Would he have been a better senator, truer to his candidacy, if he never suffered this terrible neurological trauma. All that intraparty strife for nothing. The results of the test, contaminated.

If Schumer were to clear the field for Platner—or, simply abandon his effort to run Platner off—it would spare Democrats another recriminatory cycle of factional infighting and give everyone a bit more clarity on where to go from here.

WHAT FLOATS HIS BOAT

For immediate practical purposes, it barely matters who the Democratic nominee is, and Platner’s appeal is in his willingness to challenge Collins from a new direction. If he wins—even if he propels Democrats to a Senate majority—Donald Trump will still be president, and Platneresque ideas will be stuck. His value would be in contributing to a Senate majority, which would allow Democrats to block Trump’s judicial nominees, pass messaging legislation, and little more. The only litmus tests for Maine Democratic senator should be open-mindedness to filibuster reform, and a pulse.

But that’s not what Platner and other candidates will say about their campaigns if there’s a competitive primary. If Schumer gets his way, battle lines will be drawn, and the candidates will start fighting over agendas they won’t be able to pass for several years anyhow.

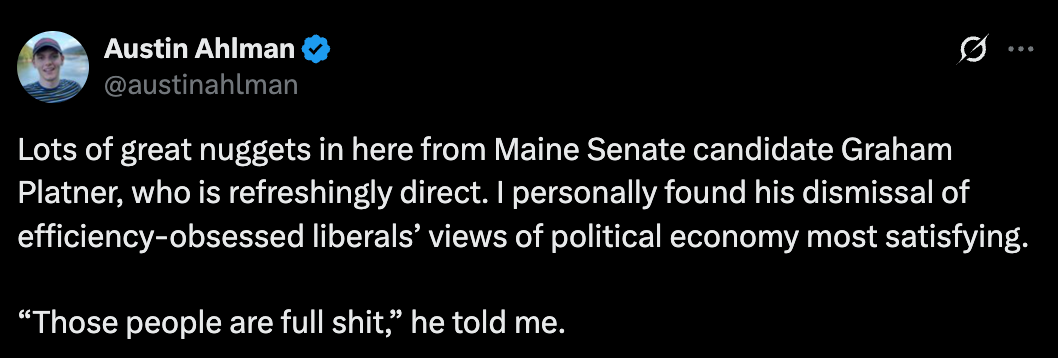

Here’s a tell: When the American Prospect interviewed Platner, it came away impressed—but also hopeful that Platner will be a tribune for progressive economic ideas if he becomes a senator.

But what is clear is that Platner’s theory of politics is fundamentally at odds with an emerging liberal orthodoxy that says Democrats need to focus on building quickly by overriding local controls over development and redistributing wealth on the back end to workers and communities that are left behind.

He pointed to his state’s famed and tightly regulated lobster industry as an example. “The state of Maine has passed laws over the years that have regulated the lobster industry in a very specific way, and it means there’s one boat, one captain, one license. Fishing can only be conducted while the captain is aboard. This has entirely disincentivized consolidation,” he explained. “The result is a half-a-billion-dollar-a-year industry for the state of Maine that has almost no corporate ownership.”

When presented with the alternative theory—that Maine should instead allow consolidation in its prize industry and redistribute wealth back to workers and their communities through other means—he bluntly dismissed its proponents. “Those people are full of shit,” Platner told the Prospect. “The distribution of resources needs to happen at the level where things are being produced.”

It’s genuinely hard to say what purpose is served by transforming the Maine Senate election into a forum for factional axe-grinding. But that goes for Schumer, too—if he wants to tamp down on Democratic infighting, he could simply stand aside.

Now, maybe Mills will get in the race anyhow and decide she shares all of Platner’s economic ideas. Maybe Schumer will get his way, but the whole primary will revolve around questions of age and experience, rather than about who’s pure and who’s tainted, who’s pragmatic and who’s quixotic. But I have my doubts.

At this juncture, I do not particularly care if Platner’s views about lobster regulation extend to the whole economy, or whether Maine lobstering regulations are good in and of themselves, or whether anti-consolidation is an important goal in general. But I do suspect that if Schumer refuses to stand down, and recruits a standard-issue liberal with broad institutional support to run against him, we will all end up whistling past the graveyard.

Instead, let’s just run the test. If Platner wins the nomination without establishment interference and loses, he’ll join the many establishment-backed candidates who’ve also lost to Collins. If he loses by an unusually large margin, or an unusually small one, that will provide good information to all of us. In either case, though, there will be no basis for counterfactuals, or stabbed-in-the-back mythologizing, from people who sincerely believe left-economic populism can win back the working class. And, of course, he might just win!

LEFT, CENTER, MOD

I spent the final year or so of my stint at Crooked Media advocating unsuccessfully for a new debate podcast meant to encompass disagreement across the broad left.

The pitch was pretty straightforward: We should produce something like Left, Right & Center, but minus Right, and its penchant for bad faith. Defeating MAGA for all time would require stabilizing the coalition spanning left, center, and parts in between. We should thus try to model what that would look like in practice: smart and honest avatars of the various wings of the pro-democracy coalition hashing out their differences publicly over time, fostering mutual comprehension, so that, come election time, a foundation of trust would make it easier for everyone to set aside internal differences and vote against fascism.

Incredibly earnest stuff.

Two years on, I’ve come around to the view that the pitch was off. Not that the show would have necessarily been bad or uninformative—it could have been very good. But it wouldn’t have served the stated purpose. It would have been luxury entertainment for high-brow types and left-of-center factionalists. In hindsight, I think the concept fundamentally overcomplicated the challenge facing the anti-Trump majority.

People of the left, center, and liberal mainstream can benefit intellectually from good-faith debate. The tagline of this newsletter is, “Because vigorous internal debate isn't a weakness—it's essential.” But the basis of a unified anti-fascist front can’t and shouldn’t be consensus across the issue space. That is not actually achievable through debate. What is achievable is proof—validation for outsiders—that dissent is welcome within the broad pro-democracy coalition. That Democratic leaders can make peace with candidates like Zohran Mamdani, and progressives can make peace with it if someone like Jeff Duncan wins the Democratic gubernatorial primary in Georgia, even as they all disagree openly. That Platner can run a campaign critical of the Democratic mainstream, mainstream avatars can explain why they think he’s wrong, and then everyone can row together toward a more pressing objective.

Debate in search of consensus, or to vindicate some ideas and defeat others, will tend to look more like this interesting but fairly bitter argument between Matt Bruenig and Kelsey Piper over the merits of cash transfers in American welfare.

This is:

A perfectly good intellectual and content-creation exercise for a magazine that aims to “make a positive, combative case for liberalism.” ✅

The kind of thing I would participate in or publish for sport, and to enrich readers. ✅

Not a great exercise for coalition building. ✅

In practice what will hold the pro-democracy coalition together for electoral purposes won’t be leftists moving right or centrists moving left, but leftists, centrists, and the people who span those camps finding their greatest common factors, and more or less forgetting about everything else, at least as a basis for voting in general elections.

FASC-BACK FRIDAY

What are the greatest common factors between left and center?

I suppose it depends on whom you ask. But the basis for broad-as-possible cooperation will almost certainly not be policy per se. It’ll be more foundational principles: majorities should govern, laws should apply blindly, all people should be treated with dignity, structural inequalities should at least be shrunk.

To the extent that socialists and democratic capitalists and welfare-state liberals agree about the future of the party, it’ll be over stuff like this, not over ancient, irreconcilable differences regarding program design, state capacity, and so on.

The broad left is awash in think tanks, including Bruenig’s, producing analysis and making arguments on behalf of various economic policy ideas that lack buy-in across the Democratic Party—in some cases because they’re too radical, in some cases because they’re too incremental.

Liberalism—as in political liberalism—might win out in post-Trump America, but not insofar as progressives and neoliberals treat their economic disagreements as of higher order than the democratic rudiments that made the New Deal and Great Society possible.

This should not be so hard. Human freedom should matter more to us than economic policy design. If it happened to be the case that fascism produced more wealth or less economic inequality than liberal democracy, it wouldn’t follow that fascism was the more moral system of government.

My own fixations on democracy protection and anti-corruption reflect this view. These things matter to me a lot on their own terms, but they are also useful as a basis for coalition politics—they are inarguable among most liberals and progressives, and thus not particularly useful as cudgels to wield in factional war. Abundance liberals and anti-corporate progressives and democratic socialists can wait out the winter of democracy arguing in circles about why their ideas are good or sucky, or they can pause to agree that, whatever policy direction the Democratic Party takes when the dark season passes, it should unshackle itself, so that it can make change quickly.

I have my ideas about what I’d like Democrats in a reconstituted democracy to do with power—but what I desperately want, much more than those things, is a fighting chance to live out my days free.

The fact that the U.S. has only two major parties makes this harder than it might otherwise be. Democrats nominate one person for president every four years, and then elections turn on whether that person is satisfying enough to everyone left of center with firmly held views on all kinds of policies.

Those people mostly don’t need persuasion through online debate, or primary election debate, or any other kind of debate. If they need to be persuaded of anything it’s to lower their expectations of how well a single candidate will ever reflect their views, and of how capable the existing U.S. system of government is of producing outcomes they support.

Persuasion happens mostly in the non-ideological or cross-pressured middle, and less on the basis of policy argumentation than on fostered impressions of which party is cooler, or more in command.

Internal argument can help create that impression, but not if it’s the bitter, factional kind. Not if it’s the kind that discourages experimentation, or chokes off fresh blood. Not if it’s the kind that allows fascists to win with less than half the vote.

I think this is missing the elephant in the room. Schumer has said his entire purpose in life is to “keep the Democratic party pro-Israel” and Platner is very hostile to the Israeli war. I don’t think Schumer or party leadership rlly care about oyster consolidation as much as they care about funding Israel. IMO Schumer would lose the general election to a R than let anti-Israel candidates win the D factional battle.

Moderates in the Democratic Party can't have it both ways. If they want lefties to support more moderate candidates when they win primaries, then they need to support lefties (or just idiosyncratic black boxes like Platner) when *they* win the primaries.